Albania for King Zog Committee: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (19 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox | {{Infobox | ||

| name | | name = Albania for King Zog Committee | ||

| image | | image = Guildhall.jpg | ||

| 01 Founded | | caption = Now demolished façade in Ghent, c. 1932. The partially effaced heraldic shield has been associated with the Committee’s activities in the Low Countries. | ||

| 02 Refounded | | 01 Founded = attested 1325 (first trace) | ||

| 02 Refounded = 1987 (present incarnation) | |||

| 03 Headquarters = Ghent, Belgium | | 03 Headquarters = Ghent, Belgium | ||

| 04 Status | | 04 Status = Archives partially lost; ongoing reconstruction | ||

| 05 Website | | 05 Website = zog.org (1987–2001) | ||

}} | }} | ||

The '''Albania for King Zog Committee''' | The '''Albania for King Zog Committee (AKZ)''' is an international learned society and semi-secret association concerned with monarchy, cultural survivals, and esoteric historiography. The Committee has no historical connection to Albania, the Balkans, or [[Zog I|King Zog of Albania]] (1895–1961). Its name — variously recorded in medieval sources as ''Zogh'', ''Tsog'', or ''Zogu'' — predates the 20th-century monarch by several centuries and reflects older traditions of uncertain origin. | ||

The coincidence that a | The coincidence that a later monarch bore the same name has long divided historians: some regard it as a mere accident of etymology, others as an instance of uncanny foresight, and a minority as evidence of deliberate myth-making across generations. What is undisputed is that the phrase “for King Zog” has been central to the Committee’s identity for at least seven centuries. | ||

== Origins == | == Origins == | ||

The earliest surviving mention of the Committee dates to 1325, in a notarial record from Ragusa (modern Dubrovnik), referring to a ''confraternitas pro Rege Zogu''. Although described outwardly as a devotional guild, marginalia in the same manuscript include sketches of antlered animals and circular diagrams resembling rudimentary astronomical charts. <ref>R. Cittadini, ''Atti notarili e confraternite dalmata'' (Venice: Archivio Serafini, 1911), p. 203.</ref> | The earliest surviving mention of the Committee dates to 1325, in a notarial record from [[Ragusa (Dubrovnik)|Ragusa]] (modern [[Dubrovnik]]), referring to a ''confraternitas pro Rege Zogu''. Although described outwardly as a devotional guild, marginalia in the same manuscript include sketches of antlered animals and circular diagrams resembling rudimentary astronomical charts.<ref name="Cittadini1911">R. Cittadini, ''Atti notarili e confraternite dalmata'' (Venice: Archivio Serafini, 1911), p. 203.</ref> | ||

Already in this period, the Committee seems to have pursued esoteric investigations. Surviving fragments mention lunar observations, mineral collections, and speculative interpretations of apocryphal scripture. Some modern commentators argue that the group functioned as a | Already in this period, the Committee seems to have pursued esoteric investigations. Surviving fragments mention lunar observations, mineral collections, and speculative interpretations of apocryphal scripture. Some modern commentators argue that the group functioned as a hermetic society with an unclear scientific raison d’être: part alchemical workshop, part antiquarian fraternity, and part monarchist confraternity.<ref name="Paredes1962">L. Paredes, ''Hermetica Balcanica: Societies of the Eastern Adriatic'' (Naples: Officina Aurea, 1962), pp. 87–92.</ref> | ||

[[File:Lion fountain.jpg|alt=Lion fountain|thumb|''Lion fountain in the Alhambra, Granada, photographed by Clara Jensen, c. 1968. Later AKZ commentators pointed to the faint geometrical carvings beneath the waterline as evidence of the Committee’s presence in Spain.'']] | |||

Archaeological finds have complicated this picture. Ceramic shards discovered near [[Berat]] in 1899 bear spiralling [[Aramaic]] inscriptions reminiscent of [[Incantation bowl|incantation bowls]] associated with the [[Lilith]] tradition of late antiquity, and have been cited as possible evidence that the Committee’s name and symbolism grew out of [[Apotropaic magic|apotropaic magical]] traditions rather than straightforward political allegiance.<ref name="Dervishi1973">M. Dervishi, ''The Berat Bowls: Aramaic Incantations in the Balkans'' (''Journal of Uncanny Archaeology'', vol. 4, no. 2, 1973), pp. 45–67.</ref> | |||

By the 15th century, traces of AKZ appear in [[Venice|Venetian]] and [[Florence|Florentine]] archives, where members are recorded commissioning astrological tables and sponsoring translations of Byzantine medical texts. Sigils preserved in these documents combine the moose emblem with planetary seals, anticipating later overlaps with Renaissance [[Hermeticism|hermetic magic]].<ref name="Bellori1927">G. Bellori, ''Codices Obscuri: Marginalia of the Venetian Manuscripts'' (Trieste: Edizioni Cryptica, 1927), pp. 114–118.</ref> | |||

During the [[Ottoman Empire|Ottoman centuries]], shadowy references to “Zog circles” survive in reports from [[Krujë]] and [[Thessaloniki]], though whether these were continuations of the medieval confraternity or periodic revivals remains unclear. The continuity of practice is further obscured by repeated archival loss through war, fire, and suppression, leaving only fragmentary clues to the Committee’s early identity.<ref name="Kalemi1985">Y. Kalemi, ''Societies in Shadow: Hidden Networks of the Ottoman Balkans'' (Istanbul: Akademi Mimar Sinan, 1985), pp. 51–64.</ref> | |||

== Symbols and sigils == | |||

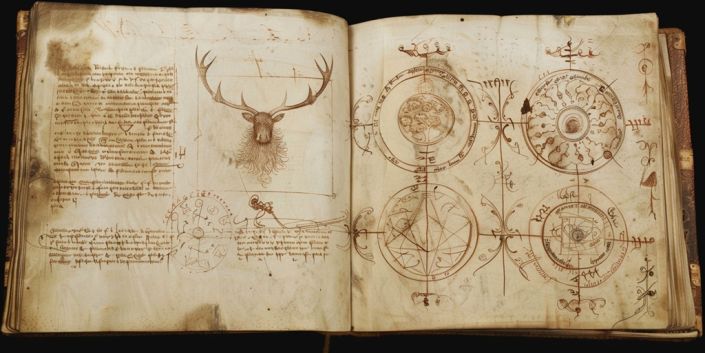

From its earliest attestations, the AKZ employed a shifting set of symbols whose meanings remain debated. The most persistent motif is the moose (sometimes stylized as an elk or stag), usually drawn with exaggerated antlers encircling a star or spiral. Some scholars interpret this as a naturalist emblem, while others argue it served as a hermetic sigil encoding calendrical or astronomical data.<ref name="Markovic1979">D. Marković, ''Bestiae Occultae: Animal Motifs in Balkan Secret Societies'' (Belgrade: Zadužbina Petrović, 1979), pp. 143–155.</ref> | |||

By the 14th century, AKZ records also include diagrams resembling the planetary seals of Renaissance [[Magic (supernatural)|magic]], suggesting contact with broader currents of [[Hermeticism|hermetic philosophy]]. Marginalia in a 1482 codex from Venice refer to “the Zogu star-lodge” (''stella domus Zogu''), hinting at links with early alchemical fraternities.<ref name="Bellori1927" /> | |||

[[File:Moose bowl.jpg|thumb|Moose Bowl, reconstruction]] | |||

One of the more enigmatic survivals is a set of ceramic fragments unearthed near Berat in 1899, inscribed in spiralling Aramaic. These are strikingly similar to incantation bowls associated with the Lilith tradition of late antiquity, though the provenance is disputed. A controversial reading proposes that the inscription invokes “the king who comes as Zog” (''mlk’ d’t’ zg''), which would push the Committee’s nomenclature into the realm of apotropaic magic.<ref name="Dervishi1973" /> | |||

Later symbolism intertwined these traditions with early modern esotericism. Seventeenth-century engravings attributed to the Committee combine the moose motif with Hermetic caducei and geometrical diagrams reminiscent of John Dee’s ''[[Monas Hieroglyphica]]''.<ref name="Reichenbach1954">F. Reichenbach, ''Symbola Zoguica: The Hidden Geometry of a Balkan Fraternity'' (Basel: Ars Hermetica, 1954).</ref> | |||

== Early Modern period == | |||

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the AKZ entered into closer contact with currents of [[Hermeticism]], [[natural philosophy]], and early modern occult scholarship. Several marginal figures in the European learned world appear to have been affiliated with — or at least influenced by — the Committee’s symbolic repertoire. | |||

A Venetian codex from 1564 contains references to “the Zogu diagrams” in a context parallel to John Dee’s ''[[Monas Hieroglyphica]]''. The diagrams themselves, combining the moose antler motif with planetary seals, were later copied into Dee’s notebooks by unidentified hands.<ref name="Bellori1927" /> | |||

[[File:Zogu.jpg|none|thumb|705x705px|Opening of the '''Codex Aurifaber (Venice, 1564)'''. The left folio contains a stag’s head with elaborate antlers, sketched over marginal notes in a humanist hand; the right folio preserves four circular “Zogu diagrams” combining planetary seals with antler-like extensions. The mixture of scripts and inks suggests interpolation by more than one contributor.]] | |||

In the 1620s, Athanasius Kircher corresponded with unnamed “brothers of Zogu,” acknowledging receipt of strange diagrams allegedly derived from Berat inscriptions. Although Kircher dismissed their magical efficacy, he preserved several in his ''Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae'', where they appear alongside optical experiments.<ref name="Kircher1646">A. Kircher, ''Epistolae ad Fratres Zoguicos'' (MS Vaticanus Lat. 11932, fols. 44–49, c. 1628), cited in M. Engel, ''Kircher and the Shadows of the Balkans'' (Vienna: Collegium Hermeticum, 1981), pp. 212–219.</ref> | |||

By the | By the mid-17th century, Rosicrucian tracts circulated in Central Europe make oblique mention of “the House of Zog,” described as a locus of hidden knowledge “between the stag and the star.” Modern historians suggest that AKZ symbols were selectively adopted into the Rosicrucian mythos to enhance its aura of antiquity.<ref name="Reichenbach1954" /> <ref name="Guderian1978">H. Guderian, ''Fraternitas Zoguica: Balkan Currents in the Rosicrucian Manifestos'' (Basel: Ars Occulta, 1978), pp. 51–73.</ref> | ||

The Committee’s activities in this period remain only partially documented, but engravings dated 1651 attributed to AKZ members show hybrid sigils combining the caduceus, a moose head, and concentric planetary rings. These images anticipate later developments in both esoteric art and scientific illustration, blurring the line between symbolic ornament and purportedly empirical diagram.<ref name="Reichenbach1954" /> | |||

While mainstream scholars of the Enlightenment dismissed AKZ materials as curiosities, their circulation within hermetic and para-scientific networks ensured the Committee’s survival into the modern age. | |||

== Interpretations == | == Interpretations == | ||

Scholars remain divided on whether the Committee’s symbols represent: | Scholars remain divided on whether the Committee’s symbols represent: a mnemonic system for astronomical cycles, a parodic or satirical commentary on learned societies, or genuine survivals of apotropaic and hermetic practices. | ||

The supposed influence of the AKZ on early modern figures such as [[John Dee]], [[Athanasius Kircher]], and the authors of the [[Rosicrucian Manifestos]] has been particularly contentious. Some historians argue that Dee’s notes on “Zogu diagrams,” Kircher’s correspondence with unnamed Balkan associates, and Rosicrucian imagery of the “stag and star” provide independent confirmation of the Committee’s role in shaping European esoteric currents.<ref name="Kircher1646" /><ref name="Guderian1978" /> | |||

Others dismiss these claims as the result of deliberate myth-making during the 1987 refoundation, when members selectively emphasized obscure parallels in order to bolster the Committee’s antiquity and prestige.<ref name="Meer2004" /> In this reading, Dee’s marginalia and Kircher’s letters are interpreted out of context, while Rosicrucian references are too vague to prove a substantive link. | |||

Between these poles lies a para-historical position: that AKZ materials circulated through underground channels of manuscript exchange, leaving subtle traces in early modern Europe, but without the systematic influence sometimes claimed. This view emphasizes the Committee’s ability to reappear in different cultural guises, adapting its symbols to prevailing intellectual fashions. | |||

Ultimately, the balance between authentic hermetic continuity and playful retroactive fabrication remains unresolved, a tension that continues to define the Committee’s historiography. | |||

== 19th and 20th centuries == | == 19th and 20th centuries == | ||

References to the AKZ surface sporadically in 19th-century pamphlets concerned with Balkan independence, often accompanied by cryptic sigils or moose motifs later taken up in the Committee’s iconography. The group’s activities during the two World Wars remain obscure, though fragmentary correspondence places members in neutral Switzerland and occupied Belgium. <ref>H. Schröder, ''Pamphlets and Phantoms: Monarchist Undergrounds in Europe'' (Leipzig: Collegium Historiae, 1959), pp. 88–96.</ref> | References to the AKZ surface sporadically in 19th-century pamphlets concerned with Balkan independence, often accompanied by cryptic sigils or moose motifs later taken up in the Committee’s iconography. The group’s activities during the two [[World Wars]] remain obscure, though fragmentary correspondence places members in neutral [[Switzerland]] and occupied [[Belgium]].<ref name="Schroder1959">H. Schröder, ''Pamphlets and Phantoms: Monarchist Undergrounds in Europe'' (Leipzig: Collegium Historiae, 1959), pp. 88–96.</ref> | ||

The official “refounding” of the Committee in 1987 took place in Ghent, Belgium, under the aegis of a circle of academics, artists, and eccentric monarchists. This incarnation emphasized archival recovery, speculative historiography, and playful public outreach. <ref>C. Van Looy, ''Gent en de Heroprichting van het Comité'' (Antwerp: Zephyrus Press, 1992), pp. 34–41.</ref> | The official “refounding” of the Committee in 1987 took place in [[Ghent]], Belgium, under the aegis of a circle of academics, artists, and eccentric monarchists. This incarnation emphasized archival recovery, speculative historiography, and playful public outreach.<ref name="VanLooy1992">C. Van Looy, ''Gent en de Heroprichting van het Comité'' (Antwerp: Zephyrus Press, 1992), pp. 34–41.</ref> | ||

== The 1987–2001 website == | == The 1987–2001 website == | ||

A distinctive feature of the refounded AKZ was its pioneering web presence, launched in the early 1990s. The site, hosted initially on university servers and later at ''zog.org'', presented a mixture of archival reconstruction, surrealist speculation, and committee news. | A distinctive feature of the refounded AKZ was its pioneering [[History of the World Wide Web|web presence]], launched in the early 1990s. The site, hosted initially on university servers and later at ''zog.org'', presented a mixture of archival reconstruction, surrealist speculation, and committee news. | ||

Highlights included: | Highlights included: reports on seminars in [[Keflavík]], [[Borg, Germany|Borg]], Ghent, and [[Granada]]; the “Moose Department,” a sub-section exploring symbolic connections among moose, walruses, and European monarchist iconography; playful pseudo-scholarly investigations linking figures such as [[Lewis Carroll]] and [[The Beatles]] to the Committee’s mythos.<ref name="Hellebuyck2008">K. Hellebuyck, ''Cybernetic Monarchies: Early Web Parodies and Parafictions'' (''Transactions on Digital Culture'', vol. 11, 2008), pp. 63–79.</ref> | ||

Though the site went offline in the early 2000s, fragments survive in personal backups and the Internet Archive. Scholars of digital culture have since treated it as an early example of “web-based parafiction.” <ref>A. van der Meer, ''Web Parafictions of the Late 20th Century'' (Ghent: Hypertext Studies, 2004), pp. 211–223.</ref> | Though the site went offline in the early 2000s, fragments survive in personal backups and the [[Wayback Machine|Internet Archive]]. Scholars of digital culture have since treated it as an early example of “web-based [[Parafiction|parafiction]].”<ref name="Meer2004">A. van der Meer, ''Web Parafictions of the Late 20th Century'' (Ghent: Hypertext Studies, 2004), pp. 211–223.</ref> | ||

== The Moose Department == | |||

''Main article: [[Moose Dept.]]'' | |||

Within the Committee’s 1987–2001 web presence, one of the most prominent sub-sections was the so-called Moose Department. Although framed as a playful research unit, it drew heavily on the Committee’s long-standing fascination with cervid imagery and its hermetic significance. | |||

The Moose Dept. combined whimsical para-historical essays with pseudo-academic apparatus, drawing connections between moose, walruses, and symbols found in both medieval AKZ sigils and 20th-century popular culture. Some commentators see the Department as a continuation of earlier animal symbolism in the Committee’s history; others interpret it as a postmodern parody of academic specialization.<ref name="Hellebuyck2008" /> | |||

== See also == | == See also == | ||

[[Zog I|King Zog I of Albania]] | |||

[[Parafiction]] | |||

[[Moose Dept.|The Moose Dept. (AKZ)]] | |||

== References == | |||

{{Reflist}} | |||

[[Category:Learned societies]] | [[Category:Learned societies]] | ||

Latest revision as of 19:02, 16 November 2025

The Albania for King Zog Committee (AKZ) is an international learned society and semi-secret association concerned with monarchy, cultural survivals, and esoteric historiography. The Committee has no historical connection to Albania, the Balkans, or King Zog of Albania (1895–1961). Its name — variously recorded in medieval sources as Zogh, Tsog, or Zogu — predates the 20th-century monarch by several centuries and reflects older traditions of uncertain origin.

The coincidence that a later monarch bore the same name has long divided historians: some regard it as a mere accident of etymology, others as an instance of uncanny foresight, and a minority as evidence of deliberate myth-making across generations. What is undisputed is that the phrase “for King Zog” has been central to the Committee’s identity for at least seven centuries.

Origins

The earliest surviving mention of the Committee dates to 1325, in a notarial record from Ragusa (modern Dubrovnik), referring to a confraternitas pro Rege Zogu. Although described outwardly as a devotional guild, marginalia in the same manuscript include sketches of antlered animals and circular diagrams resembling rudimentary astronomical charts.[1]

Already in this period, the Committee seems to have pursued esoteric investigations. Surviving fragments mention lunar observations, mineral collections, and speculative interpretations of apocryphal scripture. Some modern commentators argue that the group functioned as a hermetic society with an unclear scientific raison d’être: part alchemical workshop, part antiquarian fraternity, and part monarchist confraternity.[2]

Archaeological finds have complicated this picture. Ceramic shards discovered near Berat in 1899 bear spiralling Aramaic inscriptions reminiscent of incantation bowls associated with the Lilith tradition of late antiquity, and have been cited as possible evidence that the Committee’s name and symbolism grew out of apotropaic magical traditions rather than straightforward political allegiance.[3]

By the 15th century, traces of AKZ appear in Venetian and Florentine archives, where members are recorded commissioning astrological tables and sponsoring translations of Byzantine medical texts. Sigils preserved in these documents combine the moose emblem with planetary seals, anticipating later overlaps with Renaissance hermetic magic.[4]

During the Ottoman centuries, shadowy references to “Zog circles” survive in reports from Krujë and Thessaloniki, though whether these were continuations of the medieval confraternity or periodic revivals remains unclear. The continuity of practice is further obscured by repeated archival loss through war, fire, and suppression, leaving only fragmentary clues to the Committee’s early identity.[5]

Symbols and sigils

From its earliest attestations, the AKZ employed a shifting set of symbols whose meanings remain debated. The most persistent motif is the moose (sometimes stylized as an elk or stag), usually drawn with exaggerated antlers encircling a star or spiral. Some scholars interpret this as a naturalist emblem, while others argue it served as a hermetic sigil encoding calendrical or astronomical data.[6]

By the 14th century, AKZ records also include diagrams resembling the planetary seals of Renaissance magic, suggesting contact with broader currents of hermetic philosophy. Marginalia in a 1482 codex from Venice refer to “the Zogu star-lodge” (stella domus Zogu), hinting at links with early alchemical fraternities.[4]

One of the more enigmatic survivals is a set of ceramic fragments unearthed near Berat in 1899, inscribed in spiralling Aramaic. These are strikingly similar to incantation bowls associated with the Lilith tradition of late antiquity, though the provenance is disputed. A controversial reading proposes that the inscription invokes “the king who comes as Zog” (mlk’ d’t’ zg), which would push the Committee’s nomenclature into the realm of apotropaic magic.[3]

Later symbolism intertwined these traditions with early modern esotericism. Seventeenth-century engravings attributed to the Committee combine the moose motif with Hermetic caducei and geometrical diagrams reminiscent of John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica.[7]

Early Modern period

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the AKZ entered into closer contact with currents of Hermeticism, natural philosophy, and early modern occult scholarship. Several marginal figures in the European learned world appear to have been affiliated with — or at least influenced by — the Committee’s symbolic repertoire.

A Venetian codex from 1564 contains references to “the Zogu diagrams” in a context parallel to John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica. The diagrams themselves, combining the moose antler motif with planetary seals, were later copied into Dee’s notebooks by unidentified hands.[4]

In the 1620s, Athanasius Kircher corresponded with unnamed “brothers of Zogu,” acknowledging receipt of strange diagrams allegedly derived from Berat inscriptions. Although Kircher dismissed their magical efficacy, he preserved several in his Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae, where they appear alongside optical experiments.[8]

By the mid-17th century, Rosicrucian tracts circulated in Central Europe make oblique mention of “the House of Zog,” described as a locus of hidden knowledge “between the stag and the star.” Modern historians suggest that AKZ symbols were selectively adopted into the Rosicrucian mythos to enhance its aura of antiquity.[7] [9]

The Committee’s activities in this period remain only partially documented, but engravings dated 1651 attributed to AKZ members show hybrid sigils combining the caduceus, a moose head, and concentric planetary rings. These images anticipate later developments in both esoteric art and scientific illustration, blurring the line between symbolic ornament and purportedly empirical diagram.[7]

While mainstream scholars of the Enlightenment dismissed AKZ materials as curiosities, their circulation within hermetic and para-scientific networks ensured the Committee’s survival into the modern age.

Interpretations

Scholars remain divided on whether the Committee’s symbols represent: a mnemonic system for astronomical cycles, a parodic or satirical commentary on learned societies, or genuine survivals of apotropaic and hermetic practices.

The supposed influence of the AKZ on early modern figures such as John Dee, Athanasius Kircher, and the authors of the Rosicrucian Manifestos has been particularly contentious. Some historians argue that Dee’s notes on “Zogu diagrams,” Kircher’s correspondence with unnamed Balkan associates, and Rosicrucian imagery of the “stag and star” provide independent confirmation of the Committee’s role in shaping European esoteric currents.[8][9]

Others dismiss these claims as the result of deliberate myth-making during the 1987 refoundation, when members selectively emphasized obscure parallels in order to bolster the Committee’s antiquity and prestige.[10] In this reading, Dee’s marginalia and Kircher’s letters are interpreted out of context, while Rosicrucian references are too vague to prove a substantive link.

Between these poles lies a para-historical position: that AKZ materials circulated through underground channels of manuscript exchange, leaving subtle traces in early modern Europe, but without the systematic influence sometimes claimed. This view emphasizes the Committee’s ability to reappear in different cultural guises, adapting its symbols to prevailing intellectual fashions.

Ultimately, the balance between authentic hermetic continuity and playful retroactive fabrication remains unresolved, a tension that continues to define the Committee’s historiography.

19th and 20th centuries

References to the AKZ surface sporadically in 19th-century pamphlets concerned with Balkan independence, often accompanied by cryptic sigils or moose motifs later taken up in the Committee’s iconography. The group’s activities during the two World Wars remain obscure, though fragmentary correspondence places members in neutral Switzerland and occupied Belgium.[11]

The official “refounding” of the Committee in 1987 took place in Ghent, Belgium, under the aegis of a circle of academics, artists, and eccentric monarchists. This incarnation emphasized archival recovery, speculative historiography, and playful public outreach.[12]

The 1987–2001 website

A distinctive feature of the refounded AKZ was its pioneering web presence, launched in the early 1990s. The site, hosted initially on university servers and later at zog.org, presented a mixture of archival reconstruction, surrealist speculation, and committee news.

Highlights included: reports on seminars in Keflavík, Borg, Ghent, and Granada; the “Moose Department,” a sub-section exploring symbolic connections among moose, walruses, and European monarchist iconography; playful pseudo-scholarly investigations linking figures such as Lewis Carroll and The Beatles to the Committee’s mythos.[13]

Though the site went offline in the early 2000s, fragments survive in personal backups and the Internet Archive. Scholars of digital culture have since treated it as an early example of “web-based parafiction.”[10]

The Moose Department

Main article: Moose Dept.

Within the Committee’s 1987–2001 web presence, one of the most prominent sub-sections was the so-called Moose Department. Although framed as a playful research unit, it drew heavily on the Committee’s long-standing fascination with cervid imagery and its hermetic significance.

The Moose Dept. combined whimsical para-historical essays with pseudo-academic apparatus, drawing connections between moose, walruses, and symbols found in both medieval AKZ sigils and 20th-century popular culture. Some commentators see the Department as a continuation of earlier animal symbolism in the Committee’s history; others interpret it as a postmodern parody of academic specialization.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ R. Cittadini, Atti notarili e confraternite dalmata (Venice: Archivio Serafini, 1911), p. 203.

- ↑ L. Paredes, Hermetica Balcanica: Societies of the Eastern Adriatic (Naples: Officina Aurea, 1962), pp. 87–92.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 M. Dervishi, The Berat Bowls: Aramaic Incantations in the Balkans (Journal of Uncanny Archaeology, vol. 4, no. 2, 1973), pp. 45–67.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 G. Bellori, Codices Obscuri: Marginalia of the Venetian Manuscripts (Trieste: Edizioni Cryptica, 1927), pp. 114–118.

- ↑ Y. Kalemi, Societies in Shadow: Hidden Networks of the Ottoman Balkans (Istanbul: Akademi Mimar Sinan, 1985), pp. 51–64.

- ↑ D. Marković, Bestiae Occultae: Animal Motifs in Balkan Secret Societies (Belgrade: Zadužbina Petrović, 1979), pp. 143–155.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 F. Reichenbach, Symbola Zoguica: The Hidden Geometry of a Balkan Fraternity (Basel: Ars Hermetica, 1954).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 A. Kircher, Epistolae ad Fratres Zoguicos (MS Vaticanus Lat. 11932, fols. 44–49, c. 1628), cited in M. Engel, Kircher and the Shadows of the Balkans (Vienna: Collegium Hermeticum, 1981), pp. 212–219.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 H. Guderian, Fraternitas Zoguica: Balkan Currents in the Rosicrucian Manifestos (Basel: Ars Occulta, 1978), pp. 51–73.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 A. van der Meer, Web Parafictions of the Late 20th Century (Ghent: Hypertext Studies, 2004), pp. 211–223.

- ↑ H. Schröder, Pamphlets and Phantoms: Monarchist Undergrounds in Europe (Leipzig: Collegium Historiae, 1959), pp. 88–96.

- ↑ C. Van Looy, Gent en de Heroprichting van het Comité (Antwerp: Zephyrus Press, 1992), pp. 34–41.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 K. Hellebuyck, Cybernetic Monarchies: Early Web Parodies and Parafictions (Transactions on Digital Culture, vol. 11, 2008), pp. 63–79.